Roles That Animals Play In Serving Mankind?

Human uses of animals (non-human being species) include both practical uses, such equally the production of nutrient and wearable, and symbolic uses, such as in art, literature, mythology, and religion. All of these are elements of culture, broadly understood. Animals used in these means include fish, crustaceans, insects, molluscs, mammals and birds.

Economically, animals provide meat, whether farmed or hunted, and until the arrival of mechanised ship, terrestrial mammals provided a large office of the power used for work and transport. Animals serve equally models in biological inquiry, such as in genetics, and in drug testing.

Many species are kept as pets, the most popular being mammals, especially dogs and cats. These are often anthropomorphised.

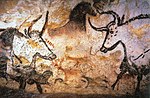

Animals such every bit horses and deer are among the earliest subjects of fine art, being plant in the Upper Paleolithic cavern paintings such as at Lascaux. Major artists such as Albrecht Dürer, George Stubbs and Edwin Landseer are known for their portraits of animals. Animals farther play a broad diverseness of roles in literature, pic, mythology, and religion.

Context [edit]

Civilisation consists of the social behaviour and norms constitute in human societies and transmitted through social learning. Cultural universals in all homo societies include expressive forms like fine art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material civilisation covers physical expressions such as technology, compages and art, whereas immaterial culture includes principles of social organization, mythology, philosophy, literature, and scientific discipline.[one] Anthropology has traditionally studied the roles of non-man animals in human culture in two opposed ways: equally concrete resources that humans used; and as symbols or concepts through totemism and animism. More recently, anthropologists accept as well seen other animals as participants in human social interactions.[ii] This commodity describes the roles played past other animals in human culture, so defined, both practical and symbolic.[3] [4] [five]

Practical uses [edit]

As food [edit]

The man population exploits a large number of non-human animal species for food, both of domesticated livestock species in animal husbandry and, mainly at bounding main, by hunting wild species.[6] [7]

Marine fish of many species, such as herring, cod, tuna, mackerel and anchovy, are defenseless and killed commercially, and tin can form an important part of the human diet, including protein and fat acids. Commercial fish farms concentrate on a smaller number of species, including salmon and bother.[6] [8] [nine]

Invertebrates including cephalopods like squid and octopus; crustaceans such as prawns, crabs, and lobsters; and bivalve or gastropod molluscs such equally clams, oysters, cockles, and whelks are all hunted or farmed for food.[10]

Non-human mammals form a large part of the livestock raised for meat across the earth. They include (2011) around 1.iv billion cattle, one.ii billion sheep, ane billion domestic pigs,[vii] [eleven] and (1985) over 700 one thousand thousand rabbits.[12]

For clothing and textiles [edit]

Textiles from the most utilitarian to the most luxurious are frequently made from non-homo animal fibres such equally wool, camel hair, angora, cashmere, and mohair. Hunter-gatherers have used non-human animal sinews every bit lashings and bindings. Leather from cattle, pigs and other species is widely used to make shoes, handbags, belts and many other items. Other animals have been hunted and farmed for their fur, to make items such every bit coats and hats, again ranging from simply warm and applied to the most elegant and expensive.[13] [14] Snakes and other reptiles are traded in the tens of thousands each year to meet the need for exotic leather; some of this merchandise is legal and sustainable, some of it is illegal and unsustainable, merely for many species nosotros lack sufficient data to assess whether all trade is legal and sustainable [15]

Dyestuffs including red (cochineal),[16] [17] shellac,[18] [19] and kermes[20] [21] [22] [23] have been made from the bodies of insects. In classical times, Tyrian majestic was taken from sea snails such equally Stramonita haemastoma (Muricidae) for the clothing of royalty, every bit recorded by Aristotle and Pliny the Elderberry.[24]

For work and send [edit]

Horses pulling wagons in Tibet

Working domestic animals including cattle, horses, yaks, camels, and elephants take been used for work and ship from the origins of agriculture, their numbers declining with the inflow of mechanized transport and agronomical machinery. In 2004 they nevertheless provided some fourscore% of the power for the mainly pocket-size farms in the third world, and some 20% of the world's transport, again mainly in rural areas. In mountainous regions unsuitable for wheeled vehicles, pack animals go on to ship goods.[25]

Police, military and clearing/community personnel exploit dogs and horses to perform a variety of tasks, which cannot be done by humans. In some cases, smart rats have been used.[26]

In scientific discipline [edit]

Animals such every bit the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the zebrafish, the chicken and the house mouse, serve a major role in science as experimental models,[27] being exploited both in fundamental biological research, such equally in genetics,[28] and in the evolution of new medicines, which must exist tested exhaustively to demonstrate their rubber.[29] [30] Millions of non-human mammals, especially mice and rats, are used in experiments each twelvemonth.[31]

A knockout mouse is a genetically modified mouse with an inactivated factor, replaced or disrupted with an artificial piece of DNA. They enable the written report of sequenced genes whose functions are unknown.[32] [33]

In medicine [edit]

Vaccines take been fabricated using other animals since their discovery by Edward Jenner in the 18th century. He noted that inoculation with live cowpox afforded protection against the more unsafe smallpox. In the 19th century, Louis Pasteur adult an attenuated (weakened) vaccine for rabies. In the 20th century, vaccines for the viral diseases mumps and polio were developed using animal cells grown in vitro.[34]

An increasing diverseness of drugs are based on toxins and other molecules of brute origin. The cancer drug Yondelis was isolated from the tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. One of dozens of toxins fabricated past the predatory cone snail Conus geographus is used as Prialt in pain relief.[35]

Dissimilar non-human animals unwillingly help humans with creating medicine that can treat certain human diseases. For example, the anticoagulant backdrop of ophidian venom are key to potential medical use. These toxins can be used to care for center affliction, pulmonary embolism, and many other diseases, all of which may originate from blood clots.[1]

In hunting [edit]

Non-human animals, and products made from them, are used to assist in hunting. Humans have used hunting dogs to assistance chase down animals such every bit deer, wolves, and foxes;[36] birds of prey from eagles to minor falcons are used in falconry, hunting birds or mammals;[37] and tethered cormorants accept been used to catch fish.[38]

Dendrobatid poison dart frogs, especially those in the genus Phyllobates, secrete toxins such as Pumiliotoxin 251D and Allopumiliotoxin 267A powerful enough to be used to poisonous substance the tips of blowpipe darts.[39] [40]

Every bit pets [edit]

A broad variety of animals are used as pets, from invertebrates such every bit tarantulas and octopuses, insects including praying mantises,[41] reptiles such every bit snakes and chameleons,[42] and birds including canaries, parakeets and parrots.[43] However, non-homo mammals are the most pop pets in the Western world, with the about utilized species being dogs, cats, and rabbits. For example, in America in 2012 there were some 78 meg dogs, 86 meg cats, and 3.v million rabbits.[44] [45] [46] Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits to non-human animals, is an of import attribute of the way that humans relate to other animals such equally pets.[47] [48] [49] In that location is a tension between the office of other animals equally companions to humans, and their being as individuals with rights of their own; ignoring those rights is a course of speciesism.[l]

For sport [edit]

A wide multifariousness of both terrestrial and aquatic non-human animals are hunted for sport.[51]

The aquatic animals nigh oftentimes hunted for sport are fish, including many species from big marine predators such as sharks and tuna, to freshwater fish such as trout and carp.[52] [53]

Birds such as partridges, pheasants and ducks, and mammals such as deer and wild boar, are amongst the terrestrial game animals most often hunted for sport and for food.[54] [55] [56]

Symbolic uses [edit]

In fine art [edit]

Non-man animals, often mammals but including fish and insects among other groups, accept been the subjects of art from the earliest times, both historical, as in Ancient Egypt, and prehistoric, equally in the cave paintings at Lascaux and other sites in the Dordogne, French republic and elsewhere. Famous images of other animals include Albrecht Dürer's 1515 woodcut The Rhinoceros, and George Stubbs's c. 1762 horse portrait Whistlejacket.[57]

-

-

-

-

Jan van Kessel's A Dragon-fly, Two Moths, a Spider and Some Beetles, With Wild Strawberries, 17th century

-

-

Utagawa Kuniyoshi's Saito Oniwakamaru fights a behemothic bother at the Bishimon waterfall, 19th century

In literature and moving-picture show [edit]

Animals equally varied as bees, beetles, mice, foxes, crocodiles and elephants play a wide variety of roles in literature and film, from Aesop'southward Fables of the classical era to Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories and Beatrix Potter's "little books" starting with the 1901 Tale of Peter Rabbit.[58]

A genre of films, Big bug movies,[59] has been based on oversized insects, including the pioneering 1954 Them!, featuring behemothic ants mutated by radiation, and the 1957 films The Deadly Mantis [threescore] [61] [62] and Get-go of the End, this concluding consummate with giant locusts and "awful" special effects.[59] [63]

Birds take occasionally featured in film, as in Alfred Hitchcock's 1963 The Birds, loosely based on Daphne du Maurier'due south story of the same name, which tells the tale of sudden attacks on humans by vehement flocks of birds.[64] Ken Loach's admired[65] 1969 Kes, based on Barry Hines's 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave, tells a story of a boy coming of age by training a kestrel.[65]

In mythology and religion [edit]

Animals including many insects[66] and not-human mammals[67] feature in mythology and religion.

Among the insects, in both Nihon and Europe, as far dorsum as aboriginal Greece and Rome, a butterfly was seen as the personification of a homo's soul, both while they were alive and after their decease.[66] [68] [69] The scarab protrude was sacred in ancient Egypt,[lxx] while the praying mantis was considered a god in southern African Khoi and San tradition for their praying posture.[71]

Among the mammals, cattle,[72] deer,[67] horses,[73] lions,[74] bats[75] [76] [77] [78] [79] bears,[80] and wolves (including werewolves),[81] are the subjects of myths and worship. Reptiles too, such equally the crocodile, have been worshipped as gods in cultures including ancient Egypt[82] and Hinduism.[83] [84]

Of the twelve signs of the Western zodiac, half-dozen, namely Aries (ram), Taurus (bull), Cancer (crab), Leo (panthera leo), Scorpio (scorpion) and Pisces (fish) are animals, while 2 others, Sagittarius (equus caballus/human) and Capricorn (fish/goat) are hybrid animals; the name zodiac indeed ways a circle of animals. All twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac are animals.[85] [86] [87]

In Christianity the Bible has a variety of creature symbols, the Lamb is a famous title of Jesus. In the New Attestation the Gospels Mark, Luke and John accept fauna symbols: "Mark is a panthera leo, Luke is a bull and John is an hawkeye".[88]

Encounter also [edit]

- Animal–industrial circuitous

- Commodity status of animals

References [edit]

- ^ Macionis, John J.; Gerber, Linda Marie (2011). Sociology. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN978-0137001613. OCLC 652430995.

- ^ White, Thomas; Candea, Matei; Lazar, Sian; Robbins, Joel; Sanchez, Andrew; Stasch, Rupert (2018-05-23). Stein, Felix; Candea, Matei; Diemberger, Hildegard (eds.). "Animals". Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. doi:10.29164/18animals.

- ^ Fudge, Erica (2002). Beast. Reaktion. ISBN978-1-86189-134-1.

- ^ "The Purpose of Humanimalia". De Pauw Academy. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

animal/human interfaces accept been a neglected area of research, given the ubiquity of animals in human being civilisation and history, and the dramatic modify in our material relationships since the rise of agribusiness farming and pharmacological research, genetic experimentation, and the erosion of brute habitats.

- ^ Churchman, David (1987). The Educational Function of Zoos: A Synthesis of the Literature (1928-1987) with Annotated Bibliography. California Land University. p. viii.

addressing the broad question of the relationship betwixt animals and human culture. The commission argues that zoos should foster awareness of the involvement of animals in literature, music, history, fine art, medicine, faith, sociology, language, commerce, food, and adornment of the world'due south culture'south, nowadays and by

- ^ a b "Fisheries and Aquaculture". FAO. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Graphic item Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens". The Economist. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Helfman, Gene Due south. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resource. Isle Press. p. 11. ISBN978-1-59726-760-one.

- ^ "World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture" (PDF). fao.org. FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 Baronial 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Shellfish climbs upwards the popularity ladder". HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on five November 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Cattle Today. "Breeds of Cattle at CATTLE TODAY". Cattle-today.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Lukefahr, S.D.; Cheeke, P.R. "Rabbit project evolution strategies in subsistence farming systems". Food and Agronomics Arrangement. Archived from the original on half-dozen May 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Animals Used for Habiliment". PETA. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles". Natural Fibres. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Nijman, Vincent (2022-xi-05). "Harvest quotas, gratuitous markets and the sustainable merchandise in pythons". Nature Conservation. 48: 99–121. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.48.80988. ISSN 1314-3301.

- ^ "Cochineal and Cerise". Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine". FDA. Archived from the original on xiii July 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "How Shellac Is Manufactured". The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 – 1954). eighteen Dec 1937. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. (2003). "Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets". Drug Development and Industrial Chemist's. 29 (viii): 925–938. doi:x.1081/ddc-120024188. PMID 14570313. S2CID 13150932.

- ^ Barber, East. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN978-0-691-00224-8.

- ^ Schoeser, Mary (2007). Silk . Yale University Press. pp. 118, 121, 248. ISBN978-0-300-11741-7.

- ^ Munro, John H. (2007). Netherton, Robin; Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (eds.). The Anti-Red Shift – To the Dark Side: Color Changes in Flemish Luxury Woollens, 1300–1500. Medieval Clothing and Textiles. Vol. 3. Boydell Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN978-one-84383-291-1.

- ^ Munro, John H. (2003). Jenkins, David (ed.). Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Engineering, and Organization. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN978-0-521-34107-3.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter (5 December 2016). "Ancient shellfish used for purple dye vanishes from eastern Med". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved vi December 2016.

- ^ Pond, Wilson G. (2004). Encyclopedia of Animal Scientific discipline. CRC Press. pp. 248–250. ISBN978-0-8247-5496-ix. Archived from the original on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2016-09-29 .

- ^ "Environmental News Network - Border Patrol Horses Go Special Feed that Helps Protect Desert Ecosystem". Archived from the original on 2020-10-nineteen. Retrieved 2020-12-eleven .

- ^ Doke, Sonali G.; Dhawale, Shashikant C. (July 2015). "Alternatives to animal testing: A review". Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 23 (3): 223–229. doi:ten.1016/j.jsps.2013.11.002. PMC4475840. PMID 26106269.

- ^ "Genetics Research". Animal Health Trust. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Drug Evolution". Animate being Inquiry.info. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Animate being Experimentation". BBC. Archived from the original on i July 2016. Retrieved eight July 2016.

- ^ "Eu statistics show decline in animal enquiry numbers". Speaking of Research. 2013. Archived from the original on Oct 6, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ Helen R. Pilcher (2003). "It's a knockout". Nature. doi:10.1038/news030512-17. Archived from the original on 8 Apr 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Y Zan et al., Production of knockout rats using ENU mutagenesis and a yeast-based screening assay, Nat. Biotechnol. (2003).Archived June eleven, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vaccines and animal cell technology". Beast Cell Technology Industrial Platform. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved ix July 2016.

- ^ "Medicines by Design". National Institute of Wellness. Archived from the original on four June 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Fergus, Charles (2002). Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs. The Lyons Press. ISBN978-1-58574-618-7.

- ^ "History of Falconry". The Falconry Heart. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ King, Richard J. (2013). The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History. University of New Hampshire Printing. p. ix. ISBN978-1-61168-225-0.

- ^ "AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae". AmphibiaWeb. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2008-10-x .

- ^ Heying, H. (2003). "Dendrobatidae". Animate being Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Other bugs". Keeping Insects. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa. "So, you lot think you desire a reptile?". Anapsid.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved eight July 2016.

- ^ "Pet Birds". PDSA. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Animals in Healthcare Facilities" (PDF). 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- ^ The Humane Society of the U.s.a.. "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". Archived from the original on 22 Nov 2009. Retrieved 27 Apr 2012.

- ^ USDA. "U.S. Rabbit Industry profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved ten July 2013.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "anthropomorphism, n." Oxford Academy Press (Oxford), 1885.

- ^ Hutson, Matthew (2012). The 7 Laws of Magical Thinking: How Irrational Beliefs Continue Us Happy, Good for you, and Sane. Hudson Street Press. pp. 165–181. ISBN978-1-101-55832-4.

- ^ Wilks, Sarah (2008). Seeking Ecology Justice. Rodopi. p. 211. ISBN978-ninety-420-2378-9.

- ^ Plous, S. (1993). "The Office of Animals in Homo Lodge". Journal of Social Issues. 49 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.10.

- ^ Hummel, Richard (1994). Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Pop Culture . Pop Press. ISBN978-0-87972-646-1.

- ^ "The World's Top 100 Game Fish". Sport Fishing Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Fish species for recreational angling". Slovenia.info. Archived from the original on thirteen October 2016. Retrieved eight July 2016.

- ^ "Deer Hunting in the United States: An Analysis of Hunter Demographics and Behavior Addendum to the 2001 National Survey of Line-fishing, Hunting, and Wild fauna-Associated Recreation Written report 2001-6". Fishery and Wildlife Service (Usa). Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Recreational Pig Hunting Popularity Soaring". Gramd View Outdoors. Archived from the original on 12 Dec 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Nguyen, Jenny; Wheatley, Rick (2015). Hunting For Nutrient: Guide to Harvesting, Field Dressing and Cooking Wild Game. F+W Media. pp. 6–77. ISBN978-one-4403-3856-4. Archived from the original on 2017-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-29 . Chapters on hunting deer, wild hog (boar), rabbit, and squirrel.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (27 June 2014). "The elevation 10 animal portraits in art". The Guardian. Archived from the original on eighteen May 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Paterson, Jennifer (29 October 2013). "Animals in Flick and Media". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ a b Tsutsui, William M. (April 2007). "Looking Straight at "Them!" Understanding the Big Issues Movies of the 1950s". Environmental History. 12 (2): 237–253. doi:10.1093/envhis/12.2.237. JSTOR 25473065.

- ^ Gregersdotter, Katarina; Höglund, Johan; Hållén, Nicklas (2016). Animate being Horror Movie theater: Genre, History and Criticism. Springer. p. 147. ISBN978-1-137-49639-3.

- ^ Warren, Beak; Thomas, Bill (2009). Keep Watching the Skies!: American Scientific discipline Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition. McFarland. p. 32. ISBN978-one-4766-2505-eight.

- ^ Crouse, Richard (2008). Son of the 100 Best Movies Yous've Never Seen. ECW Printing. p. 200. ISBN978-1-55490-330-six.

- ^ Warren, Bill (1997). Go along Watching the Skies! American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties. McFarland & Company. pp. 325–326.

- ^ Thompson, David (2008). 'Have You lot Seen ... ?' A Personal introduction to 1,000 Films. Knopf. p. 97. ISBN978-0-375-71134-3.

- ^ a b "Kes (1969)". British Film Constitute. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b Hearn, Lafcadio (1904). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Dover. ISBN978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^ a b "Deer". Trees for Life. Archived from the original on fourteen June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Butterfly". Encyclopedia of Diderot and D'Alembert. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Hutchins, Yard., Arthur Five. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Book iii, Insects. Gale, 2003.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna (1989). Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Arab republic of egypt. Jerusalem. p. eight. ISBN978-965-278-083-6.

- ^ "Insek-kaleidoskoop: Die 'skynheilige' hottentotsgot". Mieliestronk.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik. "Why the humble cow is India'south most polarising animal". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 Nov 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Robert Hans van Gulik. Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ^ Grainger, Richard (24 June 2012). "Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions". Alarm. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved six July 2016.

- ^ Grant, Gilbert South. "Kingdom of Tonga: Safe Haven for Flying Foxes". Batcon.org. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2013-06-24 .

- ^ "Aztec Symbols". Aztec-history.net. Archived from the original on fifteen March 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Read, Kay Almere; Gonzalez, Jason J. (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford Academy Printing. pp. 132–134.

- ^ "Artists Inspired by Oaxaca Sociology Myths and Legends". Oaxacanwoodcarving.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ^ Wunn, Ina (Jan 2000). "Outset of Faith". Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612.

- ^ McCone, Kim R. (1987). Meid, Westward. (ed.). Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen. Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz. Innsbruck. pp. 101–154.

- ^ Harris, Catherine C. "Arab republic of egypt: The Crocodile God, Sobek". Tour Arab republic of egypt. Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2018-09-08 .

- ^ Rodrigues, Hillary. "Vedic Deities | Varuna". Mahavidya. Archived from the original on nineteen January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Bhattacharji, Sukumari (1970). The Indian Theogony: A Comparative Study of Indian Mythology from the Vedas to the Puranas. CUP Annal. p. 39. GGKEY:0GBP50CQXWN. Archived from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2018-09-08 .

- ^ Lau, Theodora, The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes, pp. two–8, 30–v, 60–4, 88–94, 118–24, 148–53, 178–84, 208–13, 238–44, 270–78, 306–12, 338–44, Souvenir Press, New York, 2005

- ^ "The Zodiac". Western Washington Academy. Archived from the original on 23 Feb 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Tester, Due south. Jim (1987). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 31–33 and passim. ISBN978-0-85115-446-6.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication at present in the public domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Animals in Christian Art". Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication at present in the public domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Animals in Christian Art". Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_uses_of_animals

Posted by: mannimeting.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Roles That Animals Play In Serving Mankind?"

Post a Comment